Introduction

This guide will outline how to create effective educational videos, including what technology will be needed, relevant teaching and learning theories, and a step-by-step guide outlining best practices.

Why Video?

Video has numerous benefits for learning by taking advantage of both the visual and auditory channels. Videos can be organized into more easily digestible chunks and provide students with the flexibility to choose when to watch, what to watch, and the ability to re-watch. They should also provide students the option to read the video transcript or closed captioning. Students can then come to class prepared to discuss and apply what they have learned.

Videos can be time-intensive to plan, record, and edit, but they do not need to be limited to instructor-created content videos. Consider using asynchronous videos to add teacher presence outside of the classroom or have students be the creators!

Lownthal and colleagues (2012) provide examples of the wide variety of potential uses of videos:

Technology Requirements

Hardware Requirements

There is a common misconception that producing videos requires expensive equipment. In fact, you likely already have a computer or smartphone that will allow you to produce and edit videos of good quality. The following is a list of equipment you may need to create your own video.

Software Requirements

There are a number of video and audio editing software available.

TRU supports the following:

Camtasia

Camtasia is a video capture and editing software used to create audio and visual multimedia. Licenses may be available through IT Services.

You can find royalty-free and creative commons licensed images and audio clips at the following sites:

How Does Theory Support the Use of Video?

Cognitive Load Theory

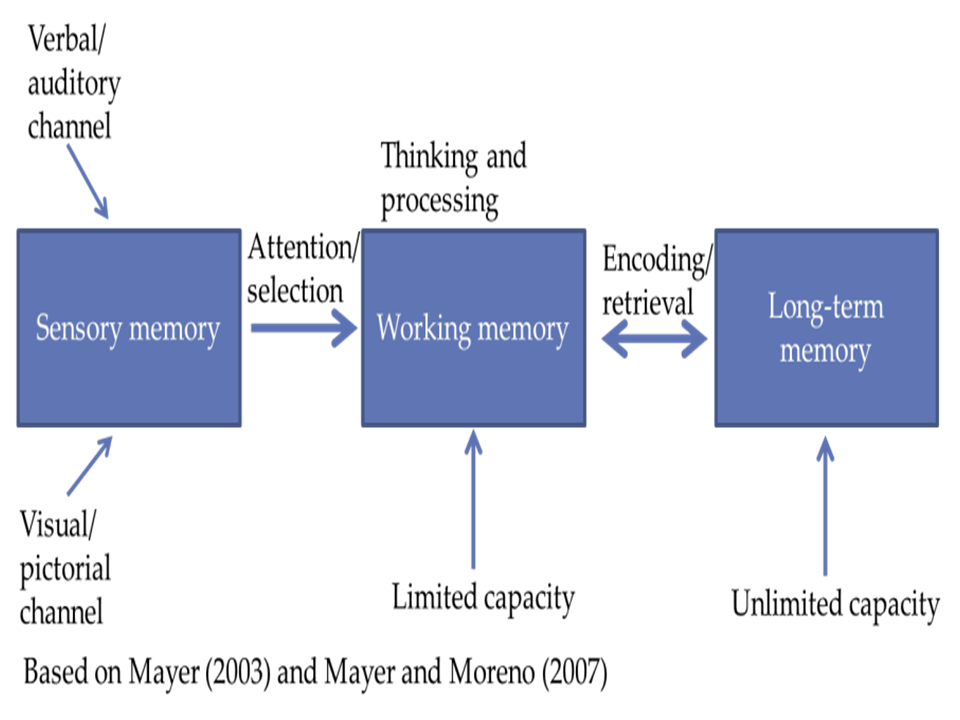

Cognitive Load Theory, originally articulated by Sweller and colleagues (1988, 1989, 1994), postulates that memory has three primary components. Sensory memory refers to transient information collected from the environment. This information can be selected for temporary storage in working memory, which has a very limited capacity. Information stored in the working memory is a prerequisite for encoding into long-term memory.

Cognitive Load Theory describes three types of cognitive load present in learning experiences:

- Extraneous Load: refers to unnecessary and distracting information

- Intrinsic Load: refers to the inherent complexity of new material

- Germane Load: refers to linking new information with current information

How our minds process and store information is an important consideration when creating educational videos. Because learners’ working memory has a limited capacity and is essential to processing information to be stored in long-term memory, it is crucial to try to reduce cognitive load and prompt the processing of only the most relevant information.

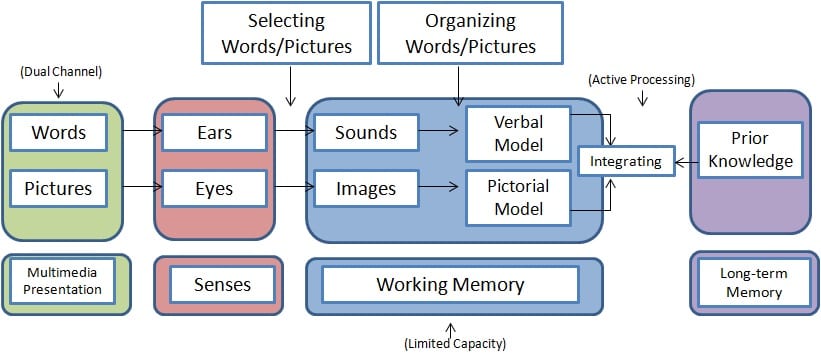

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning, building on Cognitive Load Theory, describes working memory as having two channels – visual and auditory – which, when utilized together, maximize the working memory’s capacity (Mayer and Moreno, 2003). However, managing the limited cognitive load of each channel effectively requires effective design strategies. Learning is an active process of filtering, selecting, organizing, and integrating information (Mayer, 2009).

Tips

The following recommendations will assist you to minimize extraneous cognitive load, manage intrinsic cognitive load, and optimize germane cognitive load. These recommendations draw on Mayer’s (2009) 12 Principles of Multimedia Learning. Refer to our Multimedia Design Guide for more information on the principles.

Promoting Engagement

Keep it short. Segment your videos into chunks of 6 minutes or less. This will help promote cognitive processing and engagement in learners, and allow you to create quick, concept-specific videos that can be placed in different areas in your course. Refer to our guide on splitting media into two pieces using Kaltura. If your video cannot be broken into smaller pieces, try adding time stamps so learners can more easily navigate. Additionally, ensure the visual and auditory channels are used in complementary ways. For example, people learn better from graphics and narrations than from animation and on-screen text.

Keep it simple. Utilize highlighting or annotations to signal key concepts and connection to learners. Remove extraneous information that is not relevant to the learning outcomes. This might also include removing background music or decorative images. Remove redundant information. For example, people learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics, narration and on-screen text.

Keep it real. Be yourself! Student engagement increases when instructors make the videos feel more personal and authentic by speaking conversationally and with enthusiasm. If possible, address your targeted student group. “Talking head” videos can be a nice way to add a further personal touch to your video. Keep in mind, however, that it may prove to be a distraction from other content presented in the video. Consider only having yourself appear in the beginning of the video, or reserving recording yourself for quick check-in or introductory videos.

Keep it relevant. Help situate students at the beginning of your video. What do they already need to know? What is this video going to cover? Ensure that the video is directly tied to the course learning outcomes or a particular assessment so students place value on it. Asynchronous videos do not enable direct interaction between viewers and the video creator, so try your best to anticipate possible questions, provide real-world examples, and avoid wordiness.

Promoting Active Learning:

Include guiding questions. Providing students guiding questions and encouraging them to actively note their answers has been shown to increase engagement and improve content retention (Lawson et. al., 2006).

Include formative assessment checks. Including quick formative assessment checks can help students self-regulate their learning. Refer to our guide on adding multiple choice questions within your video using the Kaltura Quiz tool.

Include features that give students control. Ensure that you have provided students with the opportunity to pause and control the movement of the video so they can review important sections. It is also helpful to include chapter headings or time stamps so students can quickly revisit a particular topic. Adding captions improves accessibility and provides an alternative to viewing the video in its entirety. Refer to our guides on using PowerPoint to add bookmarks to your video and adding transcripts or captions in Kaltura.

Include drawings or animations. Including drawings or animations can keep students more engaged than static PowerPoint slides. Consider using tools like a digital whiteboard, a lightboard, or animation software such as VideoScribe, to make your videos more engaging by actively working through problems.

Creating Your Video

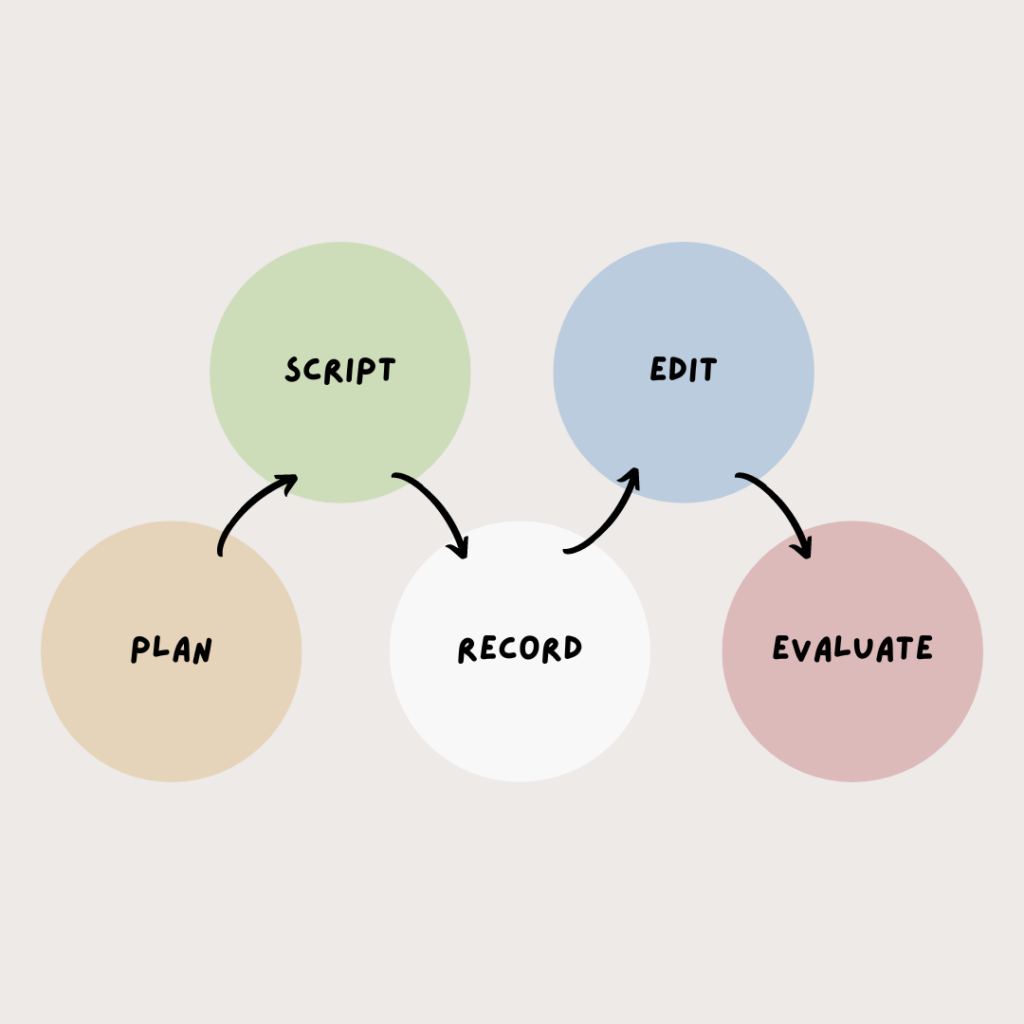

When designing a video for your course, it’s a good idea to follow a step by step process to ensure organization, efficiency and effectiveness. These steps include:

- Plan

- Script

- Record

- Edit

- Evaluate

Think of this as an iterative process rather than sequential.

Additional Resources

Teaching With Video – Act 1

Teaching With Video – Act 2

References

Brame, C.J. (2015). Effective education videos. Retrieved May 9, 2022 from http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/effective-educational-videos/.

Lawson, T. J., Bodle, J. H., Houlette, M. A., & Haubner, R. R. (2006). Guiding questions enhance student learning from educational videos. Teaching of Psychology, 33(1), 31-33. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top3301_7

Mayer, R.E and Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist 38, 43-52.